"Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth"

Franklin D. Roosevelt

We all know that what we see online can shape our behavior, influencing both the ideas we adopt and the actions we take. But can it lead to violence? Could the spread of conspiracy theories and online hate speech incite real-world attacks?

A recent study, The Relationship between Conspiracy Theory Beliefs and Political Violence, conducted by Joanna Sterling, John Voelkel, Robb Willer, and Jan-Willem van Prooijen, and published on December 12, 2024, in the Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, offers key insights. The researchers explored the connection between belief in conspiracy theories and support for political violence, using survey data from representative samples. Participants were asked about their adherence to 44 conspiracy theories and their approval of various forms of violence, both ideological and behavioral.

Sterling et al.'s study builds on a well-established body of research exploring the links between online radicalization, extremist beliefs, and violence.

Studies on hate speech and extremist discourse highlight several key dynamics. Andre Oboler (2008) examines how new technologies facilitate the spread of antisemitism and anti-Zionism, while Jessie Daniels (2009) investigates the role of digital platforms in amplifying neo-Nazi rhetoric. Regarding psychological and behavioral radicalization, McCauley and Moskalenko (2008), followed by Borum (2011), analyze the mechanisms that drive individuals toward extremism. Luke Munn (2019, 2021) further demonstrates how seemingly innocuous online interactions can contribute to gradual and widespread radicalization.

Other research focuses on recruitment strategies and online spaces. Weimann & Masri (2020) explore how extremist groups leverage social media, while Kasimov (2021) underscores the role of anonymous forums like 4chan in fostering extremist behavior. Finally, Eric Jardine (2019) examines the migration of radical discourse to the dark web, complicating efforts to monitor extremist content. Expanding on this, Lev Topor (2023) investigates how anonymous platforms like 8chan create echo chambers where isolation and peer validation fuel a cycle of radicalization, ultimately lowering the threshold for violent action.

Sterling and colleagues offer fresh insights into conspiracy theories' impact on support for violence. Unlike previous studies limited to specific theories, this research examines 44 diverse conspiracy theories varying in popularity, themes, and characteristics. The study measures three distinct forms of violence and examines temporal trends in the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and support for violence:

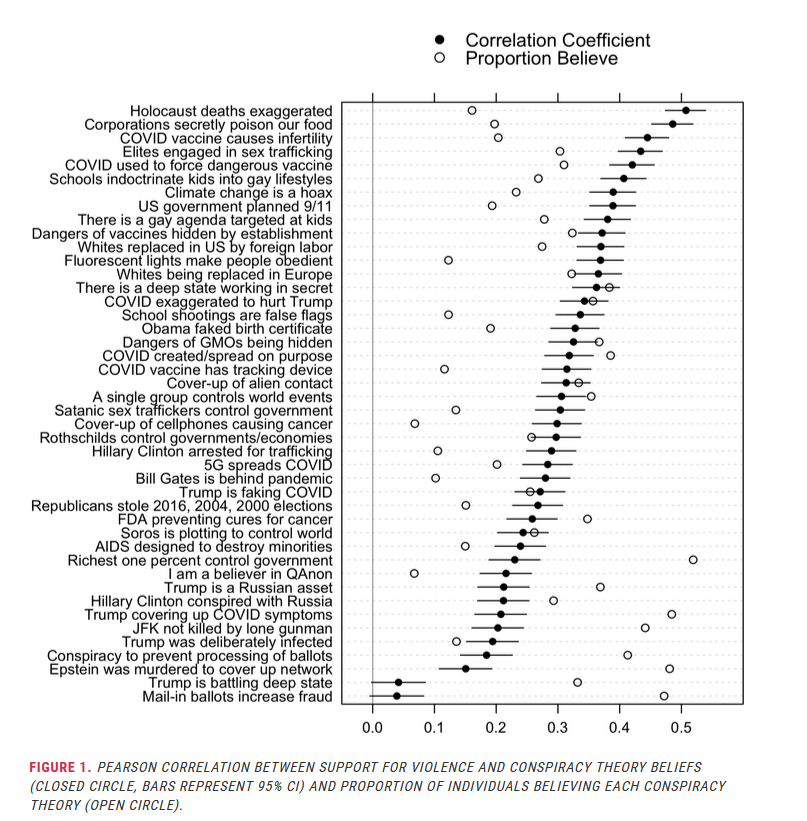

The analysis is built on two central concepts: Proportion Believe and Correlation Coefficient. These metrics help understand the dynamics observed in the study.

Proportion Believe represents the percentage of participants who endorse a specific conspiracy theory. Popular theories, such as those about JFK or 5G, show high adoption rates, while fringe beliefs like Holocaust denial remain limited to a smaller audience.

Correlation Coefficient measures the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables - in this case, conspiracy belief and violent behavior. A positive correlation indicates that as belief in a theory increases, the probability of violent behaviors also rises. However, as the results show (the average correlation between the 44 conspiracy theories and support for political violence is r = 0.30), the observed correlations remain generally weak to moderate, highlighting that other factors influence violent behaviors.

The results also demonstrate that the correlation between conspiracy beliefs and violence varies considerably across specific theories. The highest correlations notably involve theories about deliberate food poisoning (r = 0.49) and Holocaust denial (r = 0.51). Yet, the study classifies Holocaust denial as a fringe belief, given its low percentage of adherents.

This paradox illustrates a key finding: fringe theories, despite having low overall adoption rates, strongly correlate with violent behaviors. This inverse relationship between popularity and correlation suggests that less widespread, often stigmatized beliefs attract more homogeneous groups potentially more inclined toward extremism.

Sterling et al.'s study shows that Holocaust denial is a fringe theory, in the sense that it is less popular and accepted by a smaller group of people compared to more widespread theories, such as those surrounding JFK or 5G. However, among Holocaust deniers, there is a higher proportion of extremists or individuals displaying antisocial traits. This explains why the theory is strongly correlated with violent attitudes or behaviors, even though it remains relatively rare. In other words, the marginality of Holocaust denial attracts a more homogeneous and potentially more radical group, characterized by antisocial traits and a propensity for extremism. This dynamic between the theory's low popularity and its adoption by radicalized individuals strengthens its link to violence. Holocaust denial, thus acts as an ideological catalyst within extremist groups, justifying violent attitudes and behaviors.

This finding, as established in the study by Sterling and colleagues, finds a tragic illustration—though not mentioned in their work—in the case of Stephan Balliet, the perpetrator of the 2019 antisemitic attack in Halle, Germany. Radicalized online through anonymous forums, Balliet incorporated Holocaust denial rhetoric into his murderous ideology. Before attempting to enter a synagogue to carry out a massacre, he livestreamed a video in which he declared, "I am Anon, and the Holocaust didn’t happen." This statement highlights the centrality of Holocaust denial in his hate speech, used as an ideological justification for his attack.

Balliet’s attack illustrates how fringe beliefs, such as Holocaust denial, can play a structuring role in the violent actions of radicalized individuals. This case also underscores the danger of online spaces that normalize these discourses, turning them into mobilizing tools for extremist acts. Thus, Holocaust denial transcends its status as a marginal belief and becomes a decisive factor in violent radicalization trajectories.

Moreover, this marginality could also be questioned in light of recent surveys. A 2023 poll shows that 20% of young Americans aged 18 to 29 believe "the Holocaust is a myth," while 7% of the general population adheres to this view. These results suggest an increase in Holocaust denial beliefs among certain population segments, potentially reflecting a shift not captured in Sterling’s study. Therefore, while marginal globally, this belief plays a central role in some extremist groups, making the measurement of its marginality relative. This highlights the importance of a nuanced definition of marginality, which considers both global popularity and its centrality within radical subgroups.

An interesting observation in the study is that the QAnon conspiracy theory, often highlighted in the media due to the violent actions of some of its adherents, does not show as strong a correlation with support for violence (with a lower correlation coefficient compared to other theories). However, certain beliefs associated with QAnon, such as those regarding the deep state or satanic sex traffickers, show higher correlations. This distinction emphasizes that beliefs within the same conspiracy movement can vary significantly in terms of their impact on violent behavior.

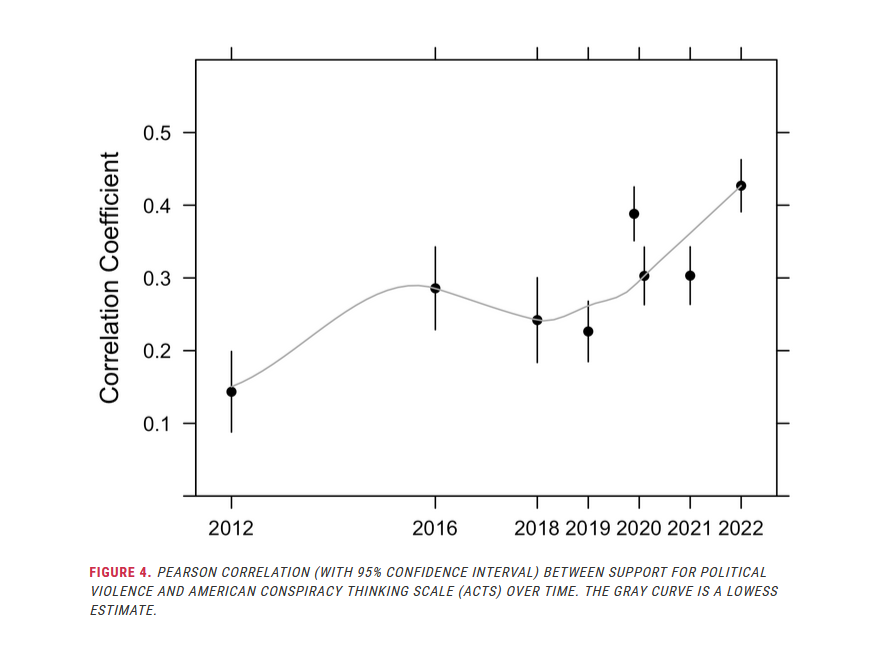

Figures 2, 3, and 4 of the study provide complementary perspectives on the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and violence. Notably, Figure 4 highlights a significant increase between 2012 and 2022, likely reflecting the growing influence of social media and global political tensions in amplifying these beliefs.

Studies converge to demonstrate that conspiracy theories and online hate are not merely inconsequential discourse. They serve as genuine catalysts for violent and extremist behaviors, exacerbating social and political tensions. While their impact varies depending on the context and the specific beliefs in question, some theories are particularly dangerous due to the characteristics of the individuals who adhere to them, often linked to violent attitudes or behaviors. In light of these challenges, an immediate and coordinated response is necessary.

For journalists and policymakers, it is essential to differentiate conspiracy theories based on their level of danger. Some beliefs, such as those involving celebrities like Taylor Swift or Kate Middleton, capture media attention without having any notable societal effects. In contrast, others, such as Holocaust denial or "Great Replacement" theories, show marked correlations with extreme behaviors. These theories should be prioritized in surveillance and counter-disinformation strategies.

Ongoing monitoring of the most harmful conspiracy theories is a crucial task. Researchers, supported by government institutions, must develop analytical models capable of identifying beliefs most likely to foster violent acts. Understanding the evolution of these theories and their popularity in specific contexts would help anticipate their potential societal impact.

However, mere exposure to a conspiracy theory is not enough to explain extreme behaviors. Believers are not a homogeneous group; they are influenced by a complex set of factors, including personal experiences, ideologies, and social environments. Interventions must, therefore, integrate this complexity and address individuals as actors shaped by multiple social and psychological dynamics.

Equally vital is the firm denunciation of violent discourse. The media and political leaders bear the responsibility of unequivocally condemning violations of social norms, such as calls for hatred or violent conspiracy rhetoric. A quick and clear reaction to such discourse can help reduce its acceptability and spread.

In addition to the immediate actions recommended in Sterling et al.'s study, sustained efforts must be made to strengthen education and awareness. Training citizens in critical thinking and providing a better understanding of historical and social dynamics can reduce their vulnerability to conspiracy narratives. Moreover, it is urgent to effectively regulate online content to limit the spread of extremist ideas while respecting fundamental freedoms.

Finally, research on the interactions between beliefs, behaviors, and environmental factors must continue. This includes examining the amplification of conspiracy narratives by artificial intelligence and social media, which play a central role in their dissemination. Conspiracy theories and online hate present complex challenges but are not insurmountable. A proactive approach, involving close collaboration between researchers, journalists, policymakers, and opinion leaders, is essential to limit their impact. By recognizing the specificity and danger of certain beliefs, understanding the complexity of individuals who adopt them, and responding firmly to violent discourse, we can protect vulnerable communities, preserve historical memory, and reinforce democratic norms.

Building a resilient society against disinformation and online radicalization is an imperative that cannot be delayed. Collective action, informed by the latest research, is our best chance to counter the devastating effects these narratives have on our democracies.

For sixteen years, Conspiracy Watch has been diligently spreading awareness about the perils of conspiracy theories through real-time monitoring and insightful analyses. To keep our mission alive, we rely on the critical support of our readers.