"Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth"

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Christine de Verdun's book challenges the narrative of her brother as a murderer

It is one of the most sinister and enigmatic true crime stories of the early 21st century, featured in the Netflix series Unsolved Mysteries.

The Dupont de Ligonnès affair began on April 21, 2011, when police discovered the decomposing bodies of five people buried under the terrace of a house in Nantes, a city in the west of France. DNA analysis was conclusive: the victims were the wife and four children of the French aristocrat Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès, who has since vanished without a trace. Autopsies revealed that all the victims: the mother Agnès, and children Arthur, Thomas, Anne, and Benoît, had been drugged before being murdered with a shot to the head. Further evidence unearthed by investigators established premeditation and heavily implicated the family patriarch, who held the title of Count.

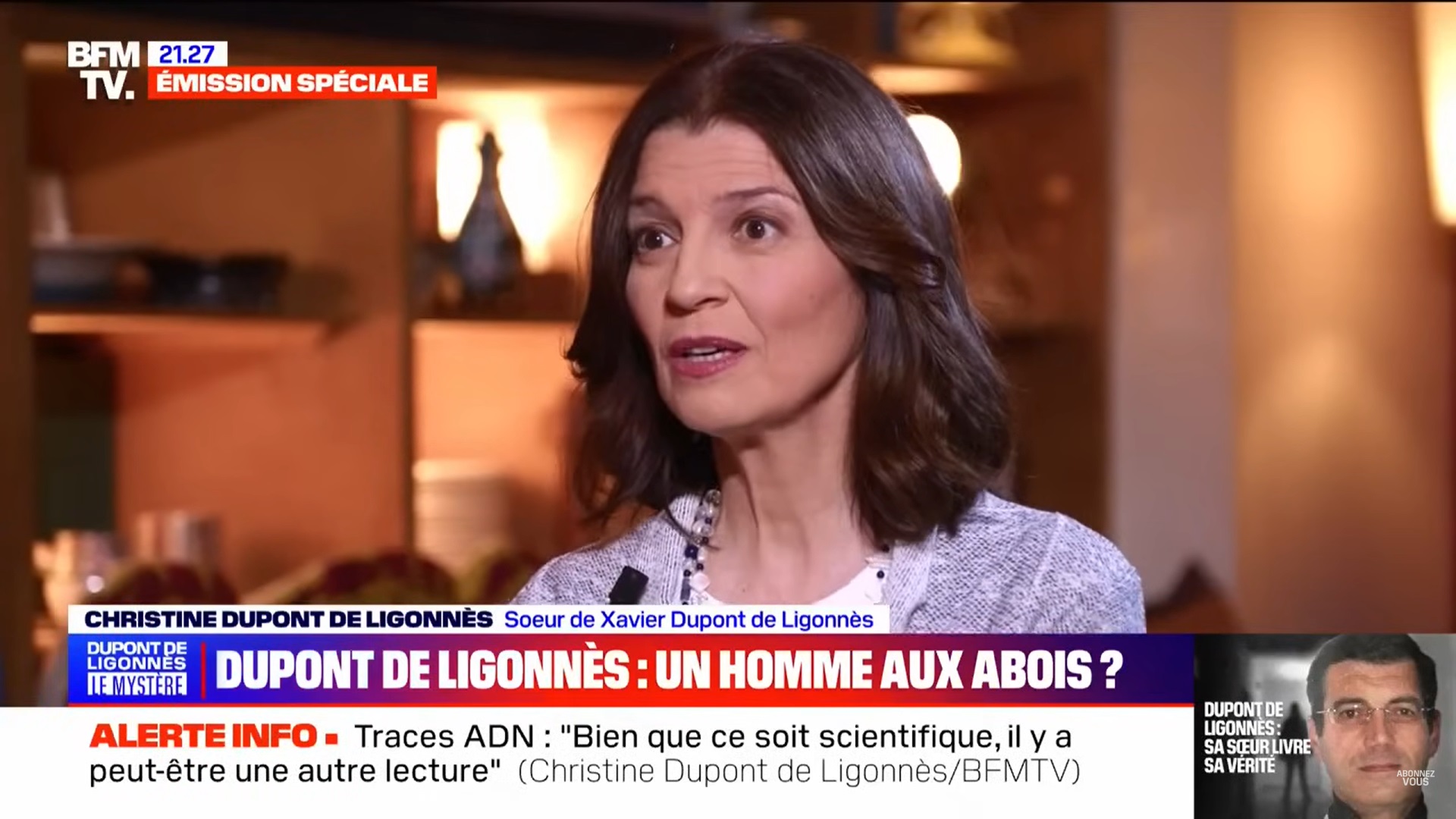

Now Christine de Verdun, the younger sister of Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès, has published a book defending the man who remains to this day the sole suspect in the multiple murders.

Xavier, My Brother, Presumed Innocent is more of an attempt at rationalization (even invoking Occam's Razor, well-known among rationalists) than a genuine counter-investigation, as it is touted on the cover of the book published in France by Harper Collins. From reading it, one can see how conspiracy theories can serve a consoling function for some. In The Real and Its Double French philosopher Clément Rosset reminds us that "nothing is more fragile than the human capacity to admit reality, to accept without reservation the imperious prerogative of the real. […] Reality is admitted only under certain conditions and only up to a certain point: if it oversteps and becomes disagreeable, tolerance is suspended. A halt in perception then shelters consciousness from any undesirable spectacle."

Indeed, despite the numerous elements that incriminate Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès, it is probably easier for his sister to believe that her nephews, her niece, and her sister-in-law are still alive than to admit the likely terrible truth that she dismisses as "inconceivable": her brother is a murderer. Christine de Verdun, who claims that "there are no real proofs" of the murders, explores the bizarre thesis of "an exfiltration" of her brother and his family "with a staging and a substitution of bodies". Her wild theories were given prime airtime on a popular weekend TV talkshow hosted by Léa Salamé on the national broadcaster France 2 on March 9, and again on March 18 on BFM TV.

Christine de Verdun has long been known for her superstitions. Along with her mother and sister, had created a prayer group claiming to receive divine messages about the Apocalypse. A police source also explains that she claimed, at one time, "to be pregnant with Lucifer". In the book she co-signs with her husband, she suggests that the plot targeting her brother goes all the way up to the highest levels of the state.

"If the Dupont de Ligonnès case is indeed a fake murder staged to hide an exfiltration, we are tempted to believe that necessarily influential people within the police or the judiciary have intervened or have been let in on the secret for the needs of the operation," de Verdun writes. "In 2011, a journalist privately told me he had learned that the Élysée was being informed daily about the progress of the investigation. Obviously, I have no guarantee of the reliability of such information, but it would support our view."

The media platforms offered to de Verdun to spread her stories about shadowy plots exonerating her prime suspect brother have been sharply criticized in France. But should we remain silent about conspiracy theories? No. Conspiracy theories are part of life; they are a societal phenomenon. It would be absurd and probably counterproductive to make them taboo subjects. However, they must be approached responsibly, within a framework ensuring the integrity of information. This excludes both complacency and the pursuit of buzz and sensationalism. If this responsibility falls on all journalists, it applies all the more so to those working for public service media outlets.

For sixteen years, Conspiracy Watch has been diligently spreading awareness about the perils of conspiracy theories through real-time monitoring and insightful analyses. To keep our mission alive, we rely on the critical support of our readers.